The Virtuoso and His Conduit: Mozart and the Modern Performer

Nico Gurdjian

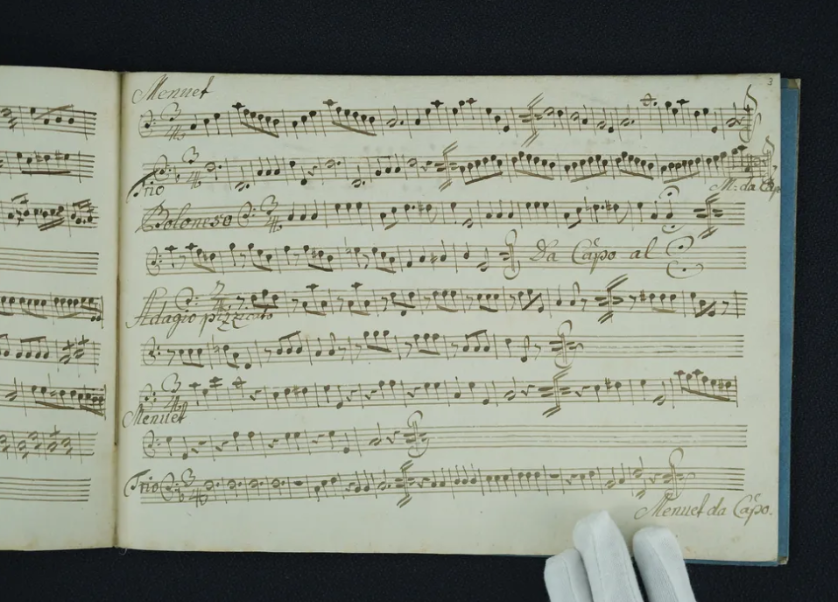

Deep in a forgotten German archive in Leipzig, a piece of Mozart's music lies hidden, untouched by the contemporary era– until now. In early September of 2024, researchers at Leipzig's music library discovered the manuscript, while organizing the latest collection of his works.

The piece is twelve minutes, coined Ganz kleine Nachtmusik, translated as Quite Little Night Music, a serenade in C. Experts who have performed and studied the composition, describe it as "an outdoor performance", a marching masterpiece. It contains seven miniature movements, two violins and a bass, for a string trio. They determined it was likely composed when he was still a boy, as it fits stylistically with similar dated pieces and he excluded "Amadeo" from his signature, which he would not add until his teens.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in Salzburg, Austria in 1756, he began composing by five, and by his teens, he had already mastered the art of symphony, opera, and sonata. To encounter a new piece of his music is to glimpse unseen corridors of his imagination. This recent discovery offers more than just a melody on paper, it is a reawakening of his voice, a fragment of a master's echo finally returning after centuries.

This new revelation leaves many questioning what happens now, without the composer himself to perform his own piece? Here the art of music transcends the written page. Just like how novels live not in the inked words but in the minds of the readers - Mozart's compositions only come to life when touched by the hands of instruments. A sheet of music is no more than a blueprint; it is up to the performers, like translators of literature, to breathe life into the notes, uncoding the phrases, deciding how each silence is weighted.

I like to think of the relationship between composers and performers as a metaphor of translation. In literature, the translator is a bridge, spanning languages, cultures, epochs, transforming one tongue into another while keeping the spirit of the original alive.

Gregory Rabassa was a renowned translator, he rendered García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude into English; a translation praised for its ability to capture the lilting magic of the Spanish original. Translators don't merely exchange words for words, they have to interpret the tone, rhythm, essence of a work - attempting to translate the untranslatable: cultural nuance, theweight of history, the pulse of people. A balancing act between loyalty and liberty, being faithful to the source and finding new life in a different tongue.

Classical music performers do not just play Mozart; they translate him. The notes on the pages are immutable, sure, but the way they are played, their breaths and emotion are in the hands of the performers. It is up to these artists to interpret, present, and revitalize the originality of each piece.

Mozart's piano sonatas are perhaps his most widely recognized works. The Sonata Facile, or Sonata No.16 in C Major, is a deceptively simple piece, a playful dance of hands and keys. But, in the hands of the performers, the interpreters, it is something else entirely. One pianist may choose to coax out the buoyant lightness, the notes begin to laugh, to skip along in tempo. Another may choose a deeply introspective path– almost melancholic. Each performance is a new translation of the same text, illuminating a new aspect, so deeply human.

Artur Schnabel was a pianist well known for his rigorously intellectual approach to music. When he played Mozart, he peeled back layers to reveal the beautiful structural genius of the melodies. His interpretations were architectural, each note placed with precision, every movement grounded in a great understanding of form. Then there was Vladimir Horowitz, a piano genius who brought Mozart to fire in a rebellious fashion. His interpretations were charged, tempestuous, an intensity that felt framatic and almost too wild for Mozart's classical restraint.

However, there is always an undeniable truth to these interpretations. A truth these musicians had found in the music that no one else had seen. Mitsuko Uchida, who plays and conducts, began her final season at Carnegie Hall Perspectives this year. She is the music, playing with incredible enthusiasm and losing herself so deeply in the act. Her Mozart translations are like water - clear, flowing, effortless. Music simply exists when she plays, unfolding naturally without artifice. Uchida takes tempos fast, but doesn't allow compromises for that, she is a force allowing the tide to pull her forwards. And that, in itself, is beautiful–a divine revitalization of a legend’s work.

There is a remarkability in how all of these interpreters stand in relation to Mozart, a man they've never met. To play the notes, to find the soul within them, to interpret the unsaid, the unseen, to make it their own. Finnish composer Jean Sibelius once said his Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43 is "a confession of the soul". I think that's what playing music is supposed to be. Bringing your own understanding and emotional vocabulary to the performance, and in doing this creating a new version of the same piece, breathing fresh life into it, making it infinite.

For now, we wait for the many more who will take on the challenge of performing this new work by Mozart. What will they find within these fresh pages? This is the beauty of translation and interpretation: the original work, whether a novel or a sonata, is not static in time. It grows and shifts, becoming anew each time it is translated and played.

Art is living in all of us, the transformation of script into sound and feeling. Mozart lives on because we do; because we listen and feel and perform his music through life, up and on again.

Listen to the new Mozart single here! Performed by Haruna Shinoyama (Violin), Neza Klinar (Violin), Philipp Comploi (Cello), Florian Birsak (Harpsichord).

Strike Out,

Nico Gurdjian

Editor: Carla Mendez

Born and raised in Miami, she is studying Psychology/Pre-Med at FIU. She likes creation myths, piano sonatas, puppet shows, and comic books. She dislikes serious letterboxd reviews, Green’s theorem, the Sicilian Defense, and whispering.