Hollywood, Happy Endings, and Humanity

Image Courtesy: The New Yorker

Recently, for a class, I’ve been watching a lot of independent French films. I didn’t begin this endeavor with many expectations, but this type of cinema definitely startled me. Overall, the movies I’ve watched for class feel more realistic than the Hollywood blockbusters to which I am accustomed. Rather than selecting the happy and exciting parts of the human experience or portraying events from a forced, positive perspective, these films dive into the entire spectrum of emotion. The most intense moments of such movies are often the most distressing and disheartening. Since the first week of class, I’ve been attempting to construct an opinion about this approach towards film. Each time I try, I come up empty. Rather than condemning one or the other here, I’ll explore these two schools of cinema–their respective outlooks on life, their promises to their audiences, and their fundamental assumptions about the role of movies in society.

A victory at the end of Star Wars: A New Hope (Image Courtesy: Star Wars News Net)

American Hollywood Megahits: Star Wars, Avengers, The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, and all the other movies I grew up with promise, at their core, happy endings. These endings are so uniquely American that the French have a term for the classic outcome of a Hollywood movie: the happy-end (pronounced derisively and in typical French fashion as “appy-en”). Before the word “Universal” even flashes across the screen, we can predict that the plot will resolve happily, leaving every character better off than at the start. Even the classic canon of blockbuster “sad movies,” from The Fault in Our Stars to Marley and Me, cannot resist placing a positive spin on things at a film’s conclusion, like the breath at the end of a sentence, promising more, implying that things will look up in the future. For the hour or two that an American moviegoer sits in the theater (or on the couch with a laptop) he or she escapes reality. Our lives are messy and confusing and overwhelming, but in Hollywood films, we find perfectly packaged, easily understood morals. The good side will always win, they promise. Helping others always leaves you better off. Even the worst life events offer some future reward. We usually don’t stop to ask whether these lessons are applicable to our own experience. What about when evil people occupy positions of power? What about sacrifice that demands everything without any recompense? What about when sad things happen and that’s just all they are–really, really sad?

Dealing with sadness in Mona Achache’s Le hérisson (Image Courtesy: The New York Times)

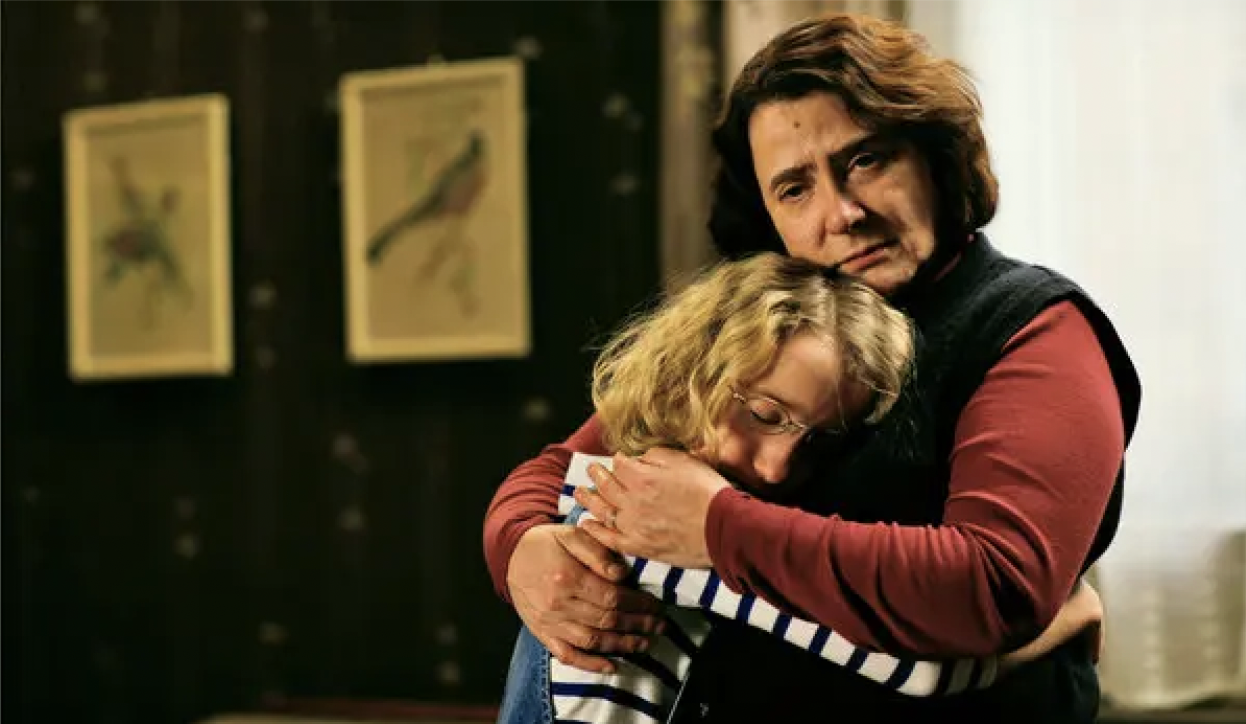

Independent French Cinema: The French movies I’ve watched don’t shy away from the sad facets of life. That’s often their main focus. For me, this preoccupation has often made watching them a profoundly uncomfortable experience. I jumped in my seat when, at the end of Mona Achache’s Le hérisson, a main character was hit out of nowhere by a car. This happened just after she had begun to find love in her extremely lonely life. Like a strange reflex, I kept waiting for the happy ending that never came. The rest of the film portrayed the other characters reeling from her death, but no happy spin ever emerged. In the same way, most other independent French movies (in my experience) depict events as happening for no reason, with no regard to human wishes. Rather than finding the good in the bad (where often there is none) they find the meaning in the pain, tragedy, and misery of life. Unlike American blockbusters, which primarily extract significance from joyful events and heroic success stories, these movies affirm that sadness is a part of the human experience and holds just as much importance and meaning as positive emotions. This suggests to me that French cinéastes search for something different in the experience of a movie. They are ready to face the discomfort of an incomprehensible life; they are prepared to ponder the absurd and perhaps even nihilistic nature of reality. They consider, truly, all aspects of what it means to be human, including suffering and hardship. They don’t want to escape; they want to live.

After exploring French film, I’ve realized that Hollywood movies I’m used to take away from the human experience. Sad things happen in a human life: loss, death, unreciprocated love, and innumerable others. Ignoring these can bring about the unfortunate habit of lying to ourselves, pretending our lives are orderly sequences of meaningful events, entirely understandable and perfectly uncomplicated. That’s not to say I don’t love Indiana Jones and Sixteen Candles and Clueless because they promise this vision of a reality both just and intelligible. The escape movies offer is valuable, and after a long day in my own life I’d usually like nothing more than to sit down and watch someone else’s–specifically, one that makes sense. I think that an ideal balance between these two movie types can be achieved. If we focus on watching both blockbusters and independent films, we can remember the difference between looking for the good and only seeing the good, so that we are equipped to deal with negative experiences. We can enjoy happy endings while remembering they are not all there is, and occasionally branch into the philosophical exploration offered by so many French filmmakers.

Strike Out,

Olivia Schmitt

University of Notre Dame

Editors: Victoria Dominesey and Maddie Arruebarrena