The Novelist’s Holy Grail

Nico Gurdjian

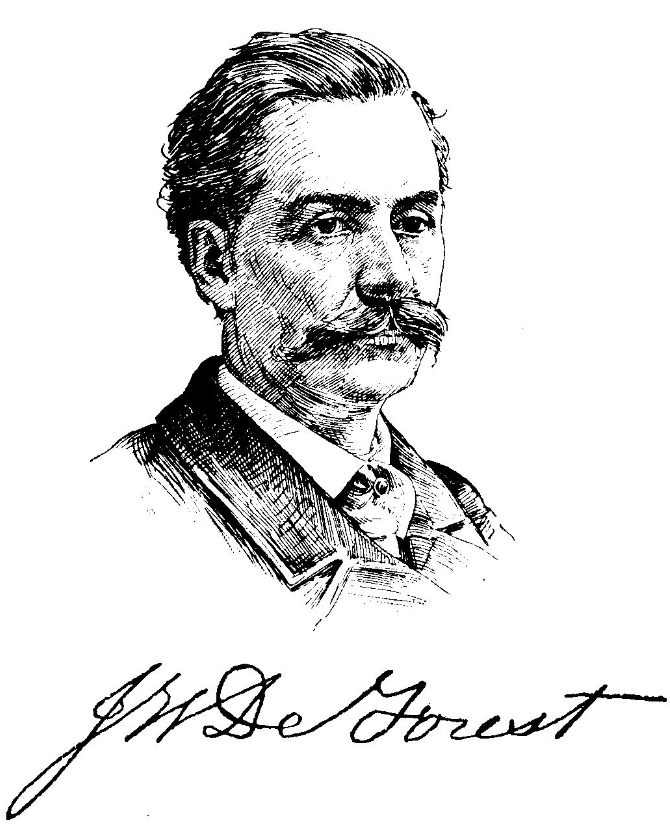

The phrase "Great American Novel" originated in an 1868 essay by Civil War novelist John William De Forest, who envisioned this novel as a packaged American society. A book that could capture "the American soul". De Forest said it was not enough for a novel to merely take place in America; it had to be distinctly American in spirit, reflecting the breadth of the country's character. He concluded that the Great American Novel had yet to be written.

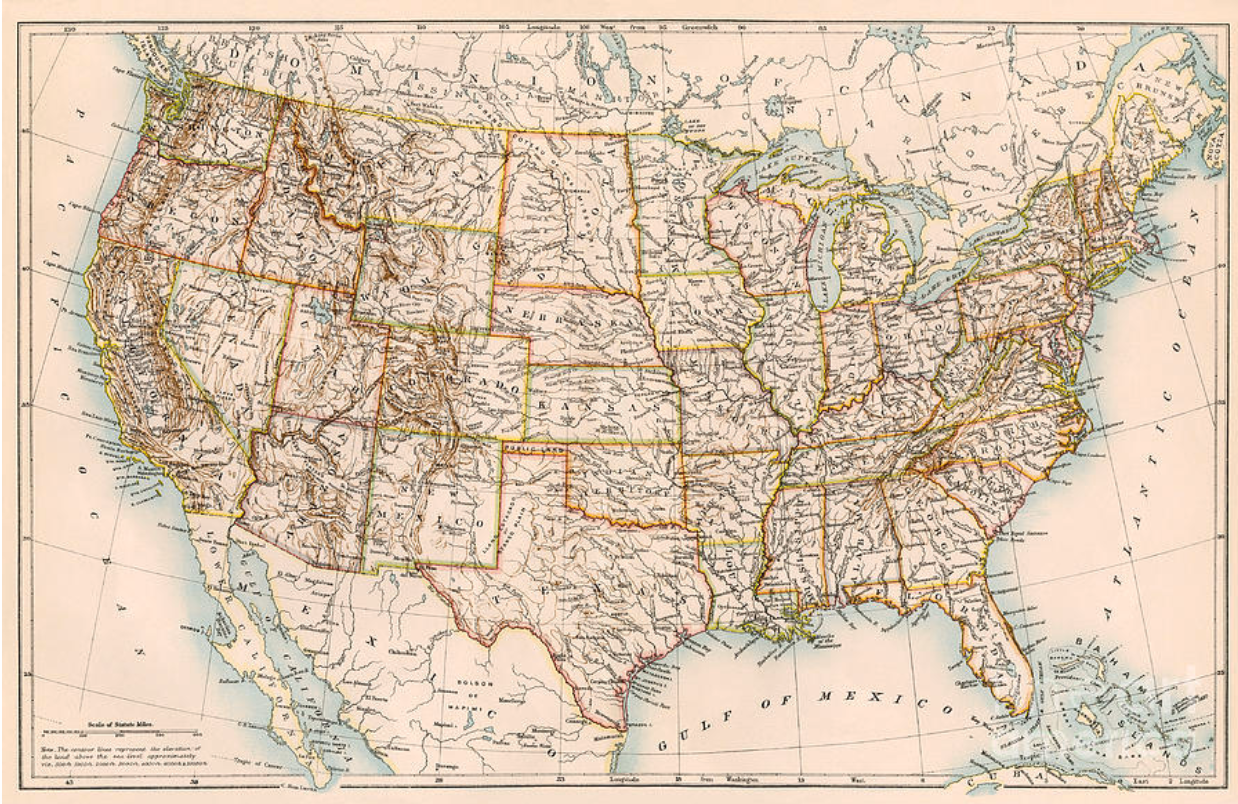

This future novel, now coined as "The Next Great American Novel", gained popularity and by the 1880s, literary circles shortened it to the "GAN". By the late 19th century, literary critic Henry James and others outlined criteria for the GAN: it should embody the entire nation rather than a single region, be democratic in spirit, and ideally, not gain its full cultural significance until later generations could appreciate its impact. This drew skepticism, many writers, like Edith Wharton, criticized its narrow perspective on what was deemed "American", and that the novel's Americanness should be incidental not central. The United States is a country built on diversity, conflicting histories, layered identities. How could one novel speak for this entire existence?

Pakistani novelist Mohsin Hamid questions the very idea, saying, "Bear with me as I advocate the death of the Great American Novel. The problem is in the phrase itself. ‘Great’ and ‘Novel’ are fine enough. But ‘the’ is needlessly exclusionary, and ‘American’ is unfortunately parochial". He critiques the desire for an American novel that is supposed to define a people or a nation, highlighting that literature by nature doesn't confine itself to national borders. He challenges the assumption that American identity can/should be distilled into one narrative. That such a project might reveal a deeper cultural insecurity. It speaks to a deeply American obsession with competition: the drive to create something definitive, unparalleled.

Considering the very fabric of American identity, it is formed by Indigenous narratives, immigrant dreams, histories of slavery and regional cultures. It becomes difficult to imagine a novel that could capture it all. Who decides what the "American experience" even is? Perhaps America's obsession with this next great novel might point to a cultural desire to package history into something easily understood and palatable. We often think of our history in terms of tidy decades and iconic moments. So this novel idea is appealing as it promises to distill an entire cultural movement into a singular literary achievement.

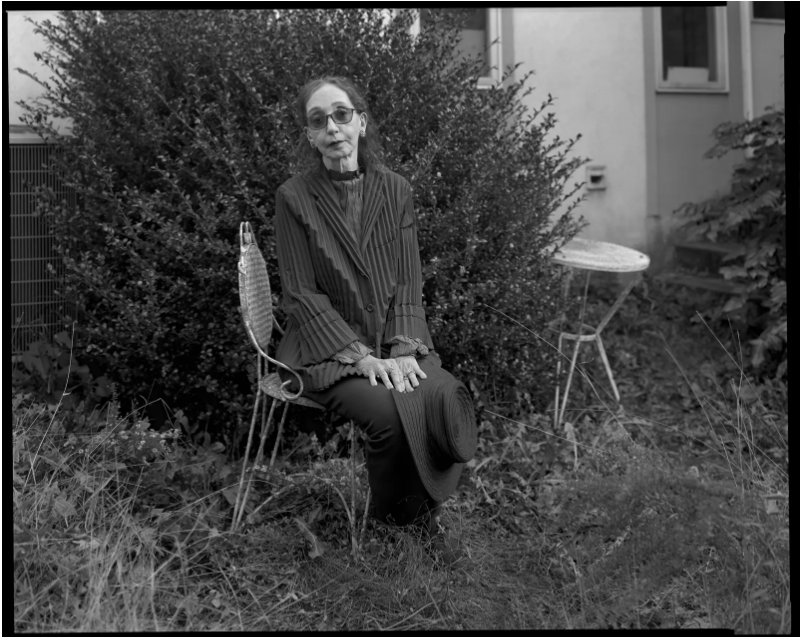

Who can take on this writing quest? Its inherent relation to masculinity is a barrier for all female writers, the narrow male-centric view that confined the description "American". Gertrude Stein felt she could not attempt it as beyond being a woman, she was a lesbian. And Joyce Carol Oates said that it wouldn't be the GAN if a woman could write it. One of the unspoken assumptions is that it can only be written by heterosexual white men. The saluted candidates are all male who have written male protagonists and are the only ones taken as contenders. A female figure serving the same protagonist role would undermine the GAN as a whole as it was believed a woman's perspective is less universal and representative of pure "American" themes. It is a cultural bias that male experiences are more capable of harnessing the American ethos. This assumption has excluded and minimized the complexity of female narratives for ages.

The daft notion of the GAN persists partly because it feels like a marker of arrival on the world stage. As American authors started to push beyond the influence of European traditions, turning toward uniquely American dialects and themes. The hope was that the young country of America could produce a novel that stood shoulder to shoulder with the works of Tolstoy or Dickens. America wanted to make a bid to declare itself mature and culturally established. Yet it led to the creation of this trap, this aspiration writers challenge with impossibly high expectations. Now America is increasingly diverse and globalized, this hope of capturing a unified experience only grows more fraught. The irony here is that literature itself often breaks these categories down. As Hamid alluded to, human beings instinctually resist the boxes we try and fit them into. And art more than anything seeks to transcend those limitations. The best stories are those that complicate our assumptions about identity, belonging, culture. Great literature is not bound by national identity, it's the human themes of love, struggle, hope, that make a novel timeless.

Despite the impossibility of this, "The Next Great American Novel" remains a siren song for authors eager to capture the complex beauty of this country. As Tony Tulathimutte put it: "a comforting romantic myth which wrongly assumes that commonality is more significant than individuality". The act of trying is a testament to the audacity that is quintessentially American. It is a reassuring purpose for the long nights of manuscript editing and ill-fated setbacks. Ultimately, the dream is more about the journey: shifting through the mosaic of voices, each unique but connected, reflecting the diversity and contradictions that define the American experience.

Candidates for the "Great American Novel":

Grapes of Wrath - John Steinbeck

A Farewell to Arms - Ernest Hemingway

Invisible Man - Ralph Ellison

On the Road - Jack Kerouac

Absalom! Absalom! -William Faulkner

My own personal favorite "Great American" novels:

Middlesex -Jeffrey Eugenides

Play It as It Lays - Joan Didion

Lonesome Dove - Larry McMurtry

Geek Love - Katherine Dunn

Beloved -Toni Morrison

Strike Out,

Nico Gurdjian

Born and raised in Miami, she is studying Psychology/Pre-Med at FIU. She likes creation myths, piano sonatas, puppet shows, and comic books. She dislikes serious letterboxd reviews, Green’s theorem, the Sicilian Defense, and whispering.