Exploring the Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd

Content Warning: Sexual Assault

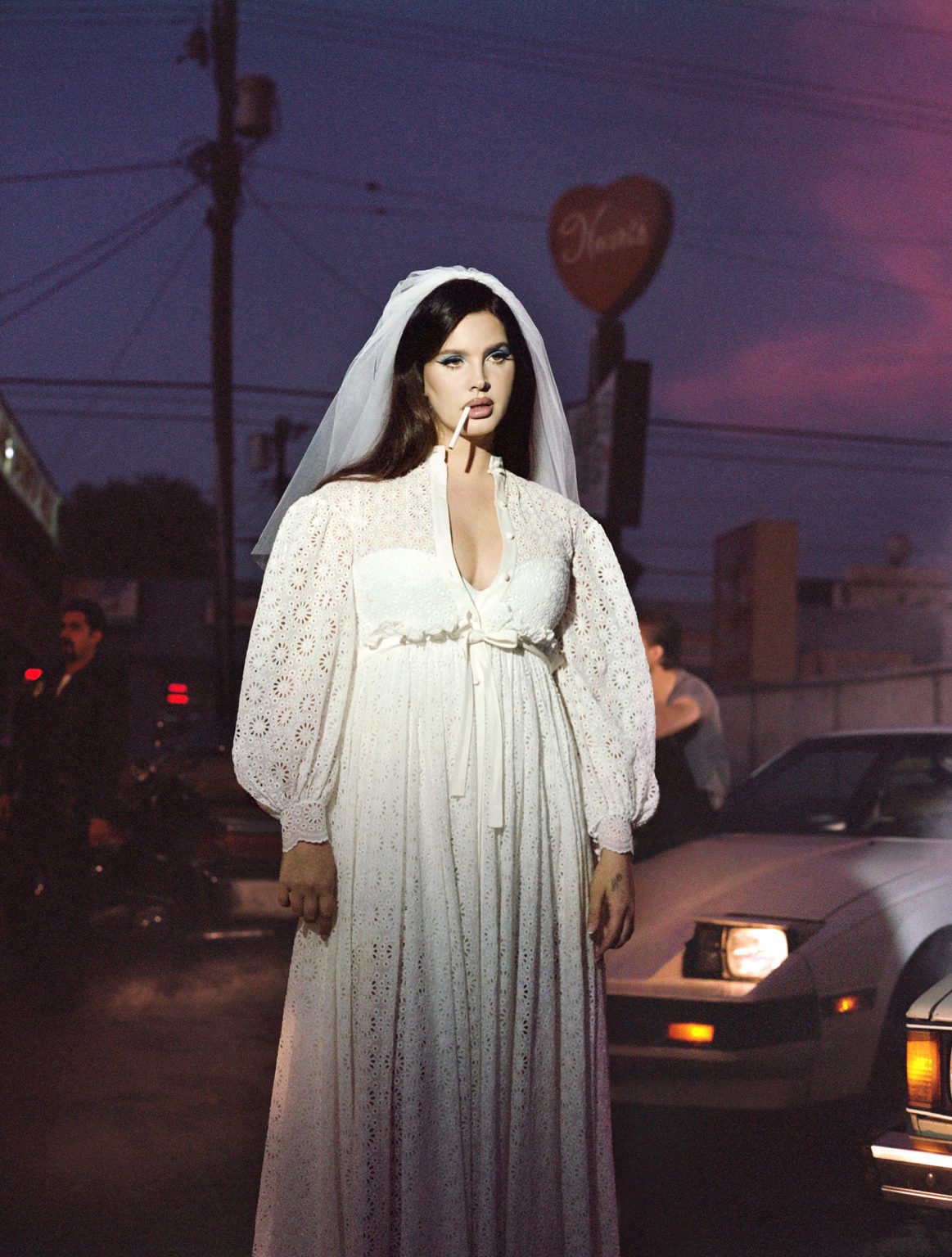

Image Courtesy: Nadia Lee Cohen for Interview Magazine (2023)

For the last decade, Lana Del Rey has consistently been one of the most interesting voices in pop music. Her dreamy sound, nostalgic aesthetics, and poetic lyrics have made a massive impact on pop culture. Today we’re talking about her ninth album, Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd (2023), and the journey that this album takes. The album itself is structured like a tunnel, and Lana pulls the listener through. It is a story of spirituality, love, and loss delivered through beautiful instrumentals, Lana’s signature breathy vocals, and her deeply introspective poetry.

Track 1: “The Grants”

The album's opening track sets the tone for everything that is to come. This song is a heartfelt tribute to Lana's family, the Grants. Lana pulls us into her world as she explores mortality, family, and spirituality. As Lana expresses her longing for a lasting legacy, we are introduced to the album’s theme of wanting to be remembered. Family is a recurring theme throughout this album, so it is only natural that we start here. The song begins with the backup singers messing up the lyrics and restarting, setting the tone for the album. Navigating life is messy and full of mistakes, and here Lana embraces imperfection. Later in the album, Lana references Kintsugi which is all about embracing imperfections, and we see that idea begin here. Considering the album as a tunnel, I think this is the perfect opener because while it is melancholic, there is a sweetness to the song. It’s almost as if the light from the entrance to the tunnel is still peeking through, right before Lana steps completely into the dark.

Image Courtesy: Los Angeles County Public Library

Track 2: “Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd”

The title of the track (and album) references the old Jergins Tunnel, built in 1927 underneath Ocean Boulevard in Long Beach, California. Sadly, the tunnel was sealed up in 1967 and has since been (mostly) forgotten. Understanding that most people don’t know it exists, Lana draws a parallel to her own fear of being forgotten. She begs listeners not to forget her like the tunnel has been forgotten and anxiously wonders when it will be her turn to fade away, as most women in music do once they reach their 30s. The relationship between darkness and light becomes a central theme for this record, representing Lana’s pain and the hope she clings to. With this song, Lana ensures that the Jergins Tunnel is never forgotten. She saves the tunnel from her own worst fear and hopes that her music will similarly immortalize her. Thematically, the song is very similar to her hit “Young and Beautiful,” as both tracks see Lana wonder when she will age out of favor.

Image Courtesy: Brian Addison for Long Beach Post

Track 3: “Sweet”

In the third track, "Sweet," Lana explores darkness a little bit more, showcasing its role as a safe and familiar space for her. The lyrics "You can find me where no one will be, in the woods somewhere, in the night" show how darkness provides her privacy and safety. At this point in the album, we are still at the beginning of the metaphorical tunnel before the light makes its way in. "Sweet" also continues the theme of family. In the lyrics, Lana yearns for a husband and the traditional family structure. However, she clarifies that she is "a different kind of woman” and does not conform to societal expectations. Here, Lana highlights her individuality and her desire to carve her own path, even within a familial context.

Track 4: “A&W”, Track 5: “Judah Smith Interlude”, Track 6: “Candy Necklace”, & Track 7: “Jon Batiste Interlude”

Continuing through the tunnel, these songs go deeper into Lana’s pain. In "A&W," Lana contrasts the innocence of childhood with the harsh realities of adulthood. Like the album, this song is structured like a tunnel with a delicate and moody piano ballad that transitions into an aggressively playful bop. This sonic transition from darkness to light reinforces the album’s themes. Lana contemplates how her age will impact her perception as well as the experience of being “an American whore”. In this first piano half, Lana is disillusioned with love and feels unimportant in her relationships, accepting the title of a “whore” or “side piece.” Lana also sings about rape culture in this song and how it further pushes her towards accepting the title of the American whore. She sings, “I mean, look at my hair. Look at the length of it and the shape of my body. If I told you that I was raped, do you really think that anybody would think I didn't ask for it? I didn't ask for it. I won't testify, I already f****d up my story.” Here, Lana highlights how many victims of sexual assault don’t come forward because they know justice will not be served. She acknowledges how being a beautiful or sexual woman is seen as a reason the victim deserved the assault, and there is a sense of helplessness in these lyrics. Because she has been sexual on her own terms in the past, she already has a story nobody will believe, and there is no point in even testifying. This lyric could also refer to how many victims are not ready to come forward right away, and the fact that they have waited to come forward already means they have ruined their story. These lyrics also leave us wondering if being an “American whore” is something Lana has really chosen for herself or if it is a title ascribed to her by judgmental outsiders. Perhaps Lana has only become this stereotype because she believes it is the only thing people will see or accept her as. In the second half of "A&W," Lana sings, "You can be my light.” This lyric has a double meaning, representing both the person she sings about as a source of joy while also using light to represent the potential for heartbreak, as later explored in the song "Kintsugi."

In the next track, "Judah Smith Interlude," Lana seeks religious guidance. This interlude is a sermon that touches on the album's themes, most notably the distinction between love and lust. Judah Smith preaches about love and family, contrasting the lyrics of "A&W." People seek out spiritual guidance in dark or desperate times, so this track shows us how lost Lana is feeling and how important spirituality is to her peace. Moving further into the tunnel, "Candy Necklace" is a song about distraction and release. The candy necklace is a triple entendre here, symbolizing youth and sweetness (an actual candy necklace), love and lust (alluding to sexual choking and the neck as an erogenous zone), and suicide as a means of escape (with the necklace, in this case, being a noose and the candy being the sweet release of death). A candy necklace is also an interesting metaphor for love, as it starts off fun and sweet but will quickly dissolve into nothing if it is enjoyed. It’s not real jewelry, but instead a cheap childish replica. After resigning herself from true love on “A&W,” here Lana obsesses over a cheap but sweet version that leaves her suicidal. “Jon Batiste Interlude” furthers this introduction of light, mentioning the early morning and the lyrics “You're the sun dancing to the moon.” These songs take us into the darkest parts of the tunnel while introducing the themes of light, religion/spirituality, and desire.

Image Courtesy: Lia Clay Miller for Billboard (2023)

Track 8: “Kintsugi” & Track 9: “Fingertips”

In these next two tracks, Lana guides the listener through the middle of the tunnel, where the light at the end is finally visible. "Kintsugi" is a song about the universal experience of repeatedly having your heart broken. Lana sings about the importance of these experiences in our lives, knowing that a heart was made to break. Kintsugi is a Japanese art form where broken pottery is repaired with gold. Here, Lana finds comfort in knowing that she can rebuild her life into something even more beautiful than it was before, just like kintsugi. She knows that she has to crack for the light to get in, and this revelation leads us toward the end of the tunnel. Lana also touches on her fear of being forgotten in this song, this time from a new perspective. She sings, “They sang folk songs from the '40s, even the fourteen-year-old knew "Froggie Came A-Courtin." How do my blood relatives know all of these songs? I don't know anyone left to know songs that I sing. That’s how the light gets in.” Here she recognizes the staying power of music. The fact that her young family members remember old folk songs reinforces to Lana that the legacy she wants to leave can be found in her family and in her music. She recognizes the sadness of something being forgotten while highlighting the joy of it being discovered.

In "Fingertips," Lana shares her deepest thoughts in a stream-of-consciousness song that blends music and poetry. Continuing the familial theme, this song dives deep into Lana’s emotional baggage. Lana opens up about several life experiences, such as being raped at the age of 15, a boyfriend who died young, her own suicide attempt, and being sent away to boarding school. These experiences add further context to her state of mind in “A&W” and her complex relationship with love, lust, and family. Here, Lana draws from the themes of "Kintsugi," using the light in her life to provide comfort and strength. “Fingertips” also continues Lana’s yearning for a traditional family, although, in this song, she wonders if she could handle motherhood given her psychological struggles. "Fingertips" serves as a cathartic release, allowing Lana to say what’s on her mind, leave behind her emotional baggage, and move through the tunnel with a newfound sense of freedom.

Track 10: “Paris, Texas”

The tenth track, "Paris, Texas," is a huge turning point in the album. Lana mentions her home of Venice, California, hinting at where her journey through this tunnel will end. "Paris, Texas" marks the true introduction of light, both lyrically and sonically. The sound is less melancholic than previous tracks, and for the first time on this album, she seems happy. Lana mentions places in America that share a name with large European cities (Paris, Texas, Florence, Alabama, and Venice, California). By naming these lesser-known places, Lana emphasizes her love for America as well as the people and things she loves. Lana's love for and complex relationship with America is a huge recurring theme in her previous albums, and here Lana expresses that America at large is her home. The line "When you know, you know. It's time to go" shows her clarity and peace. Lana recognizes that it is finally time to depart from the darkness and move forward.

Fun Fact: The Waffle House that Lana went viral for “working at” earlier this year is in Florence, Alabama (the staff gave her a name tag and shirt as a joke, and it got memed into oblivion). Her brother lives in Florence, so this song really is about places with significance to her and not simply wordplay with European cities.

Image Courtesy: Nadia Lee Cohen for Interview Magazine (2023)

Track 11: “Grandfather please stand on the shoulders of my father while he’s deep sea fishing”, Track 12: “Let The Light In”, & Track 13: “Margaret”

These tracks continue the themes of family, spirituality, and resilience. In "Grandfather," Lana yearns for spiritual guidance (like she did with the Judah Smith interlude) and calls upon her deceased grandfather for a sign and for protection. This song feels optimistic and hopeful, unlike previous tracks that touch on grief. Lana also reflects on her public image and career, saying that she knows her true self despite the critics saying she was manufactured by a record label. This highlights the authenticity of the songs on the album, showing that they come from Lizzy Grant, not her persona Lana Del Rey. "Let The Light In" is a romantic song about fighting for a way back inside, either literally or metaphorically, and connects back to the theme of home. The fight mentioned in the song is quickly resolved as Lana sings, “Look at us, back at it again.” Given the context of “Kintsugi” and the turbulent relationship described, there is an undertone that this love could potentially lead to heartbreak despite how romantic it is. Despite the risks, Lana now knows the importance of stepping into the light and embracing love. The concept of "Kintsugi" is put into action in the song "Margaret," which details the love between Lana's producer, Jack Antonoff, and his wife, Margaret Qualley. Knowing that Margaret is Jack's first love following a serious five-year relationship, the lyrics show that you can rebuild your life after experiencing something destructive. It showcases the metaphor of Kintsugi in action, where the mending process results in a beautiful, strong, new life. These 3 tracks showcase Lana's ability to embrace love and light, her need for a spiritual connection, and the power of picking yourself back up.

Image Courtesy of: Lia Clay Miller for Billboard (2023)

Track 14: “Fishtail” & Track 15: “Peppers”

The fourteenth track, "Fishtail," is a gloomy song with trap influences where Lana realizes that someone she loves takes her for granted. The song opens with "Don't you dare say that you'll braid my hair if you don't really care," portraying the act of braiding hair as emotionally intimate and sweet. Lana further reinforces this innocence with references to skipping rope. Skipping rope and braiding hair are both very youthful, innocent activities, which is how Lana feels about her lover. She loves him sweetly and innocently, contrasting how he likes her when she’s sad. The fishtail braid also serves as a metaphor for love, something seemingly complex that is actually pretty simple if you take the time. While we are towards the end of the tunnel now and surely in the light with Lana singing about sunbathing, this song shows that sadness and heartbreak will always be a constant, even in better times. The song is also in retrospect, showing the clarity Lana now has and further showcasing that the darkness is behind her.

"Fishtail" leads us to "Peppers," a cheeky, confident track that contrasts the previous song. The song’s chorus, sampled from “Angelina” by Tommy Genesis, references Angelina Jolie as a sex symbol in her role as Lara Croft, changing braiding hair from something sweet & intimate to something overtly sexual. While a Fishtail braid requires care and attention, the braid in “Peppers” is carelessly referred to as “a fat criss-cross in the back somewhere.” In “A&W,” Lana presents her sexuality in a way that is painful and destructive, but “Peppers” is sexual in a way that feels free. The song’s title refers to Lana and her boyfriend listening to The Red Hot Chilli Peppers, which paints a picture of them being cool and laid-back, highly contrasting “Fishtail,” where she is listening to the Queen of Jazz Ella Fitzgerald instead. Unlike “Fishtail,” Lana is confident in this track, expressing how love, music, and poetry come naturally to her by saying she writes hit songs “like all the time.” Another parallel between “Peppers” and “Fishtail” is how both songs reference skinny dipping. In “Fishtail,” Lana wants to skinny dip in her man’s mind, meaning she wants to know him as best as possible and get as much of him as possible. In “Peppers,” she wants to skinny dip in her own mind, showing her growth in confidence and her new perspective. “Peppers” also calls back to Lana’s 2018 track “Bartender.” In “Bartender,” Lana sings about taking desperate measures to ensure her privacy, such as buying a nondescript vehicle in the middle of the night to avoid her fame. She flips this in “Peppers,” and the midnight truck drive becomes something fun and casual. The vulnerability of “Fishtail” leading into the coolness of “Peppers” showcases how Lana is able to bounce back from pain and step into the light again.

Image Courtesy: Nadia Lee Cohen for Interview Magazine (2023)

Track 16: “Taco Truck x VB”

We are now finally out of the tunnel with the album's final track. Like "A&W," this song is structured as a tunnel, with a darker first half transitioning into a brighter second half. In the first half, Lana paints a picture of her current life, being in love with her boyfriend whom she met at a taco truck and going through nicotine withdrawal. She addresses her critics, acknowledging that they already hate her and therefore will “spin” anything she does negatively. The lyrics about nicotine withdrawal suggest that Lana is in the process of change but still relies on her vices. This connects to a later lyric where she clarifies that despite her perceived improvement, she still has the capacity for violence. Additionally, Lana is known to include very specific references in her lyrics to comment on the current cultural climate. On previous albums, she does this with references to Kanye West, iPads, an iPhone 11, crypto, and the California wildfires. On this album, she references vaping and COVID-19 as a way to date the music and comment on changing times. Long gone are the cigarette-filled Tumblr days that Lana once ruled; in this modern era, her cigarette has been replaced with a vape. She regards COVID very flippantly, which is a little jarring to hear, but that is the point. In this new era, a pandemic is no big deal, and what used to be a staple of her image —a cigarette— has now become an electronic copy. These tiny, thoughtful nuances are what complete any Lana album, and it is no coincidence that these last 2 songs include references to the changing world. The end of this album is about Lana looking forward instead of backward, a perfect place for her to subtly embrace these cultural changes, whether positive or negative. As “Taco Truck” fades out, we are taken through the tunnel of the song (featuring a voicemail from Margaret Qualley talking about the mundane, domestic things she did that day) into a new version of Lana's fan-favorite 2018 track "Venice Bitch." In previous tracks, Lana sings about the places that aren’t home (The north country, Rosemead when she’s really at the Ramada), but now at the end of this journey, she knows where home is to her. Lana is from New York and grew up around Lake Placid (as referenced in this song), but as an adult, the home she has made for herself is in California. Throughout this album, she acknowledges where she came from, and through this final track, she lets us know where she’s going. Both are still home, even if where she came from isn’t her physical home anymore. The lyrics of “Venice Bitch” sampled in this song connect back to previous themes of family, with Lana singing about a sweet, simple life with her partner where she sits “on the stoop with the neighborhood kids.” In this new version of the song, Lana includes references to dropping acid and never dying, showcasing how she wants to live a calm, domestic life while remaining wild at heart, which is a huge topic on her previous album Chemtrails Over The Country Club. This song also connects back to the loss of innocence introduced on “A&W,” with Lana singing, “Back in the garden, we're getting high now because we're older.” On “A&W,” the loss of innocence is deeply painful, but here we see Lana happy and simply acknowledging it as part of growing up. With “Venice Bitch,” Lana mentally and physically returns home, ending the album perfectly. Throughout the entire album Lana taps into nostalgia with references to her older music, such as her 2019 track “Love song.” Nostalgia has always played a big role in the allure of Lana Del Rey, but with this album she uses the nostalgia of her own older music, further cementing and acknowledging the legacy she is here to establish. “Venice Bitch” is also a perfect choice as it contains a reference to Tommy James & The Shondells’ 1968 track “Crimson & Clover,” doubling up on the nostalgia.

With light as such a strong theme in this album, it is only fitting that Lana ends up at the sunny Venice Beach. It is also worth noting that while much of Lana’s discography is influenced by hip-hop (even saying in her song “Blue Jeans” that she grew up on hip-hop), these hip-hop elements don’t appear until the final 3 tracks. With hip-hop being something Lana grew up on, this sonically signals to us that Lana is returning home. Family, love, home, and music have been central to Lana's joy and identity, and to her, Los Angeles represents all of those things—the same city where the titular Jergins Tunnel resides. As Lana says in her song “Get Free,” this album takes the listener out of the black and into the blue. Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd is out now on all platforms.

Image Courtesy: Lia Clay Miller for Billboard (2023)

Strike Out,

Writer: Richard Rentz

Edited by: Reanna Haase and Sarah Harwell

Orlando

Richard Rentz is a writer for Strike Magazine Orlando. He’s an avid record collector who loves skiing, playing Animal Crossing, and rewatching “Bottoms”. You can reach him at rentzrichardm@gmail.com or on Instagram at @rentzrichardm.